Since its acclaimed premiere in Birmingham in 1846, Mendelssohn’s Elijah has undoubtedly been one of the most successful and influential oratorios ever written. The most important reason for this is undoubtedly the dramatic structure of the work. Mendelssohn sets standards for the genre as a whole by transforming the epic biblical account into a compelling plot with a brilliantly conceived dramatic structure.

This enables him to capture the stages of the biblical events, such as drought, fire, rain, and the appearance of God, in gripping musical images. The strings unmistakably paint a picture of the licking flames, the humility of the converted people resounds like a chorale from the choir, and the roar of the waves after the redeeming rain has perhaps never been captured more vividly in music.

From the very first moment, it is impossible to escape the dramatic pull of the action when Elijah prophesies a long drought over dark brass chords, thus raising the curtain. He turns militantly against the Baal cult of the people in the kingdom of King Ahab and challenges the followers of Baal in an ingeniously conceived, almost operatic scene: A burnt offering is to be made, but no fire is to be lit. The Baalim pray to their god, but their increasingly wild invocations, interrupted by Elijah’s mockery, fade away unheard in effective general pauses.

With a simple, heartfelt prayer, Elijah finally causes fire to fall from heaven, thus revealing who the true God is. This demonstration of power converts the people, so that after three years, rain finally falls again. But this triumph is short-lived: the queen seduces the people and incites them against Elijah in a tense dialogue.

Faced with the whipped-up, murderous crowd, Elijah is forced to flee into the desert and resignedly accepts that he has ultimately failed. Humanly approachable and vulnerable, he seeks God’s presence and, in a mystical scene on Mount Horeb, is granted it. The appearance of God, colorfully depicted by the choir and orchestra, is preceded by wind, earthquake, and fire, and only then does he approach in a quiet, gentle whisper. Strengthened by this experience, Elijah gives a final sermon and finally ascends to heaven in a blaze of light.

PERFORMERS

Altonaer Singakademie choir

SinfonieOrchester Tempelhof orchestra

Bogna Bernagiewicz soprano

Susanne Veeh soprano

Inka Stubbe alto

Veronika Wolgast alto

Karl Hänsel tenor

Andreas Preuß tenor

Henryk Böhm bass

Tom Kessler bass

Emil Thomas treble

Camerata Bergedorf chamber orchestra

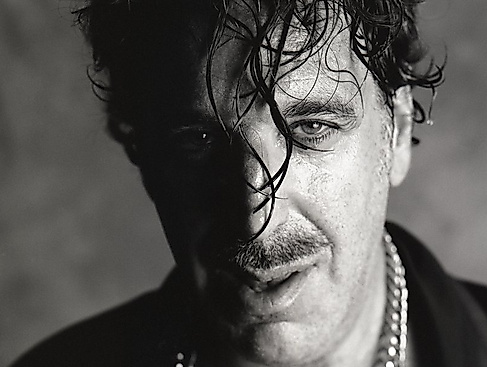

Christoph Westphal director

PROGRAM

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Elijah